The Constraints That Create Autonomy

The conventional wisdom about autonomy is simple: remove constraints. Get out of people’s way. Let them figure it out. Trust them to run.

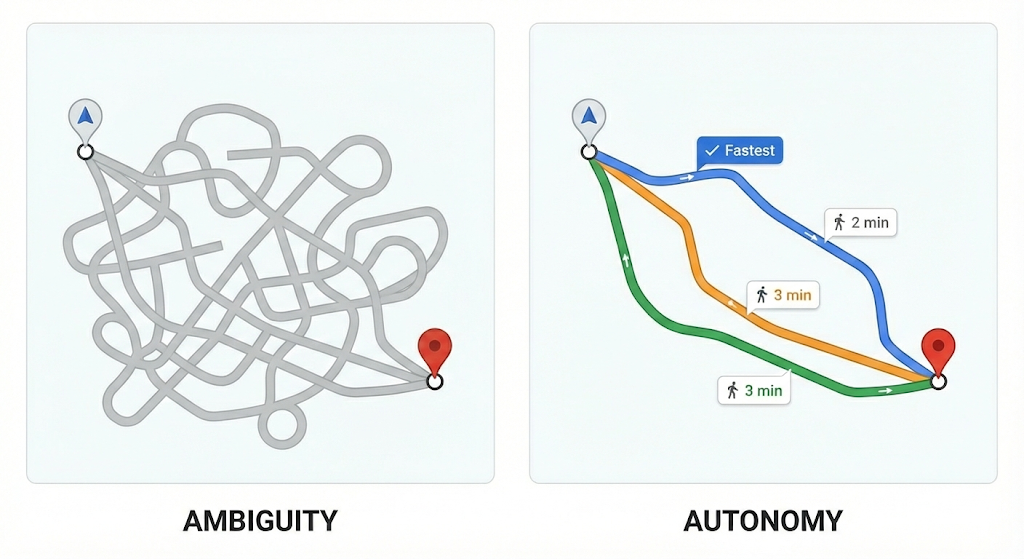

But this often backfires in a specific, predictable way. Teams think they have autonomy. What they actually have is ambiguity.

Everything Was Fine Until It Wasn’t

A talented engineer or team starts work on something important. They get buy-in from their immediate manager and teammates. They build something thoughtful and technically sound. Then – often late in the process – they discover they needed to involve stakeholder X, or that priority Y had shifted, or that framework Z required different architectural trade-offs.

Their work gets redirected, stopped entirely, or needs significant rework.

From the team’s perspective, this feels like micromanagement. Someone swooped in and interfered with their work. They had autonomy, and then it was taken away. The organizational bureaucracy got in the way of their execution.

If you’ve been on the receiving end of this, you know how demoralizing it is. You did everything right. You built something you were proud of. And then it got killed – or worse, it limped forward in some compromised form that nobody loves. The next time you start a project, you’re gun-shy. You start seeking more approvals, more consensus, more air cover. The thing that was supposed to feel empowering – autonomy to just execute – turns into learned helplessness about navigating the organization.

Plot Twist

Here’s what I’ve learned from watching this pattern play out – and, honestly, from sometimes being part of causing it: these teams weren’t suffering from too many constraints. They were suffering from too few.

The constraint they were missing wasn’t someone checking their work or approving their decisions. It was clarity upfront about organizational direction, stakeholder alignment requirements, and decision-making frameworks.

Real autonomy – the kind where teams can execute fast and own outcomes – comes from providing the right constraints early enough that teams can navigate without constantly seeking permission or discovering landmines after they’ve already committed.

Why Your Startup Days Felt Simpler

This tension is clearest when you contrast startups with large companies.

At my startup, autonomy was straightforward. The framework for moving forward was simple: get your co-founders bought in and execute. The constraint set was small and knowable. You could hold the entire organizational context in your head.

At Microsoft, Facebook, Google – or any large company – the framework was more complex. Strategy happened at multiple levels. Stakeholders weren’t always obvious. There were frameworks for privacy review, for compliance, for coding standards, for technology choices. You could execute flawlessly on a technical level and still faceplant because you didn’t understand which constraints mattered for your particular problem.

The teams that move fastest in big companies aren’t the ones with the fewest constraints. They’re the ones with the clearest understanding of which constraints apply to their work.

Constraints Worth Having

A few things consistently help:

Clear organizational direction. Not just “what we’re building” but “what we’re not building and why.” I’ve always loved the “non-goals” section in design docs – it forces you to think about the boundaries of what you’re building and get aligned on them with stakeholders. It also keeps conversations focused and avoids bikeshedding on things you’ve already decided not to pursue.

Known stakeholders and alignment requirements. Not everyone needs to be involved in every decision, but everyone needs to know who needs to be involved in which kinds of decisions. The teams that get surprised by stakeholders late are usually the ones who didn’t establish that clarity upfront.

Clear, well-socialized decision-making frameworks. Large organizations develop these over time – often for good reasons, like preventing past failures. When teams understand the frameworks (even if they don’t love them), they can design solutions that work within the system instead of fighting it. The best frameworks push decisions as close to the work as possible, with oversight only where it’s genuinely useful – not as a permanent gate.

Transparent priorities and trade-offs. Teams should feel like they can pick their own priorities – within the framework of the larger organization’s goals. When they understand organizational priorities clearly enough, they can make local trade-off decisions that roll up correctly without needing to escalate everything.

Not Just Your Manager’s Problem

Creating this kind of autonomy isn’t just a manager’s job. Every leader at every level needs to think about it.

Managers can help identify and socialize strategy, stakeholders, and frameworks. But the culture of clarity needs to be broader than that. Senior engineers leading projects need to think about it. Staff engineers shaping technical direction need to think about it. Anyone making decisions that affect other people’s work needs to think about fostering autonomy through clarity.

The leaders who create real autonomy aren’t the ones who say “figure it out yourself.” They’re the ones who say “here’s where we’re headed, here’s who needs to be aligned, here’s how we make decisions – now go own it.”

This also means being intentional about where you do apply influence. Every time a leader intervenes – redirects a project, adds a stakeholder, changes a priority – there’s a cost. Even when the intervention is correct, it can erode the team’s sense of ownership. So it’s worth asking: what am I actually trying to accomplish here? What’s the minimum I can do to accomplish that? Can I provide this guidance upfront next time, so the team can navigate it themselves?

The goal is to front-load the constraints that matter and then get out of the way.

More Rules, More Freedom

More constraints should feel like less freedom. But the right constraints – provided early and clearly – create more space to move than ambiguous freedom ever does.

People often confuse the cause of their lack of autonomy. They assume constraints are what’s blocking them, when the missing constraints are what’s creating the interference they’re experiencing.

The teams that move fastest don’t have the fewest rules. They have clarity, not ambiguity.